The green valleys and snow-capped mountains of Kyrgyzstan paint a serene landscape, nested between pastures where livestock graze and colorful rural villages dotted with traditional housing. Against this idyllic backdrop, an insidious tradition lurks - one that sees women and girls ripped violently from this mountain haven to face a new, unexpected life not of their choosing.

Bridal abduction, known as “ala kachuu” in the local Kyrgyz tongue, persists despite determined efforts to eliminate its grip on certain rural communities. It unfolds with shocking speed - a young woman running errands outdoors or doing chores, is suddenly set upon by a group of men. In an instant, she finds herself grabbed, shoved into a waiting car, and whisked off without warning to face a forced marriage ordained not by choice, but by compulsion.The trauma takes hold immediately - panicked screams giving way to desperate pleading as their attackers remain unmoved to pity. The captive may be a neighbor’s daughter familiar since childhood, or a complete stranger soon to share bed and board by decree rather than affection. Backroads and country lanes provide an easy escape from view, the kicking captive carried into her unknown future.

Some public abductions even occur brazenly amidst witnesses, so engrained in parts of Kyrgyz culture that few intercede and well-trod tradition numbs any outrage. In rarer cases, door locks prove no barrier as homes are invaded to drag daughters straight from their families - lest time or obstacles prevent stealing their future. A wedding dress awaits the stunned young woman, now prisoner behind lace and linen.

Bridal Abduction: An Urgent Human Rights Issue in Kyrgyzstan

A Stolen Life

For kidnapped brides in Kyrgyzstan, the moment their freedom is ripped away sets in motion a new existence entirely out of their hands, fate now subject to the whims and temperaments of complete strangers.

The methods used to force compliance vary - some rely on physical and emotional abuse to essentially torture women into submission. Others leverage social stigma and honor myths to corner victims psychologically. But every stolen future shares the common trait of a life irrevocably altered without consent.

The Captor’s Wrath

“I screamed and fought so hard on the long drive, beating the driver with my fists” recalls Ainura. “When we arrived, my ‘husband’ dragged me inside and struck me hard. He said he paid a bride price and I was now his property to do with as he pleased.”

Ainura’s experience is far from unique. Many who resist, refusing either sexual or domestic servitude, find themselves victims of violence from both their abductor and his relatives. Beatings, starvation diets, being locked outdoors in the winter chill, or being confined to closets for days become weapons to overpower captive women’s resistance. Some describe being tied to furniture when their captor sleeps, lest they escape.

“His family held me down at knifepoint while he raped me over and over that first night, laughing at my weeping,” agonizes 17-year-old Ryskul, her spirit crushed. “I pray now only for death to take me.”

In a heartbreaking number of cases, victims’ bodies are indeed broken along with their will. Those killed outright by “husbands” enraged at refusal make macabre headlines as mortality sparks interest where suffering does not. As in life, women’s voices go unheard except for scream echoes marking their deaths.

Psychological Torture

Physical violence, however gruesome, retains a straightforward motive - sheer terror overpowering resistance. But words too wield impact enough to subjugate brides rejecting family pressure after a kidnapping. Emotional strong-arm tactics often leverage visceral fear of social stigma.

“When I wouldn’t stop crying, my father-in-law called me selfish and wicked,” agonizes Atyrkul, recalling her abduction trauma. “That no man would ever touch me, I’d wind up cast out and destitute.”

Shame around purity and virginity retains a powerful grip in segmentation Kyrgyz circles. Families apply this leverage against kidnapped daughters and sisters, weaponizing fear of being culturally blacklisted as ‘unclean goods’ if they abandon new in-laws. With young lives invested so heavily in eventual motherhood and family standing, it proves a potent threat.

Some captors even compel local imams to invoke religious language, preying on female piety. Citing scripture selectively, they are ordered to comply or risk spiritual censure from pillars of their community and even Allah - terrifying prospects for young Muslim women. Between social death within the mortal world or beyond, many submit believing all escape routes are closed.

The Bargain for Survival

For some victims, the sustained physical and emotional abuse ultimately ‘succeeds’ in transforming captivity into long-suffering bonding with tormenters. Through a kind of Stockholm Syndrome, terror gives way to traumatic attachment as a survival mechanism.

“After two months his anger turned to small kindnesses when I obeyed”, tells Elmira. “As my body and spirit broke, he seemed pleased and granted me more food and privilege. Now I cling to him, as he is my world entire.”

When all outside feedback worsens conditions, the slightest mercy can feel like salvation. Some women relate to being given an actual bedroom rather than a floor mat after menial labor and repeated assaults. They rationalize violence as discipline for their own good, now emotionally dependent on captors shouldering responsibility for lives rendered forfeit everywhere else.

This paradoxical refuge with abusers articulates the depth of control exerted in weaponizing social values against rape victims until they identify with aggressors. Having lost everything beyond captivity’s walls, the slightest light within morphs into a blinding sun they orbit simply to survive.

The Dimmed Future

However secured through brutality, coercion, or surrender, the end result remains unchanged for Kyrgyzstan’s stolen daughters - a life utterly hijacked, its potential left unrealized against the winning bid of whichever stranger claims her as carnal chattel. Whether by fist or forced signatures, they are remanded to domestic bondage bereft of personal liberty.

Those enduring violence will one day resemble the living ghosts now limping about village streets, their youthful spark absent after decades of dwelling in a home not of their choosing. Victims broken by social threats are forever burdened with the shame complexes of their parents and elders beating them. And Stockholm hostages forge traumatic bonds with captors, emotionally chained for years.

Behind cold statistics around bridal theft waits the discovered truth - thousands of individual women seeing futures, talents, and dreams blotted out forever when consent gave way to contempt for their sovereign choice. Each represents karmic black marks upon Kyrgyzstan’s conscience. Their stolen lives ultimately measure the moral progress yet to be made.

Cultural Roots Run Deep

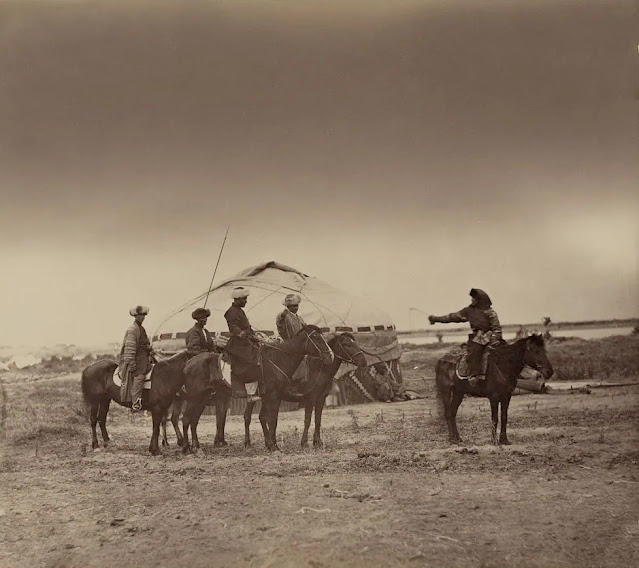

|

| A woman (first from right) and four men on horses preparing to "kidnap" her. Kyrgyz steppe, between 1871 and 1872 |

Ala kachuu’s tenacious grip on parts of Kyrgyz society stems from patriarchal views deeply embedded over centuries despite modern legal prohibitions. Many rural communities continue to tacitly enable the practice through complicity or actively perpetuating myths that defend its “necessity”.

For them, the trauma inflicted is either ignored or justified as a reasonable price for tradition. Draconian beliefs around purity and honor hold battered women hostage as much as fists and threats. And ambivalence from authorities stems either from not valuing female rights or fear of stirring conflicts by challenging the old order.

This courage deficit at all levels propagates the kidnapping crisis even as Kyrgyzstan continues gradual social liberalization in other spheres.

Patriarchy and “Honor” as Tools of Oppression

“We are upholding our honored forefather’s ways - just as they took brides, so shall we,” proclaims Almazbek, a weathered village elder. “A woman's obedience keeps harmony.”His words underline the deeply patriarchal veins still influencing regional attitudes, with masculine prerogative deemed supreme. Women occupy lower social stations, and their chief function as vessels for passing down immutable traditions. They belong not to themselves but to fathers, husbands, and clerics.

“It brought such shame when my sister refused her captor’s bed,” laments young Kanykey, echoing the prevailing mindset. “I told her she must stay, or no good family would want her after.”

These internalized norms exert crushing pressure on kidnapped brides and skew communal reactions to their plight. An assaulted woman refusing her attacker is judged as being at fault. The disgrace of her rejection, however involuntary the marriage, is believed to stain innocence and ruin reputations.

With chastity prized above personal autonomy, victims accede feeling cornered. And their parents, while perhaps initially outraged, frequently urge acquiescence once marriage rites are complete. The communal ‘damage’ is done, and honor now demanding she remains - cementing the victors’ position.

Religious Pretexts

Male entitlements and female duties are often couched as articles of faith by regional religious leaders, weaponizing theology to help justify ala kachuu’s ongoing practice.“Allah intended for women to obey husbands just as men must provide,” contends an imam from Osh Province where bridal thefts remain high. “If she disobeys after the wedding sacrament, it is the same as turning from righteousness.”

While moderate clerics condemn any coercion, such religious rationalizing gives indispensable cover to the most conservative believers. It enables them to defend not only ala kachuu itself but its aftermath - forced labor, confinement, and rape following the kidnapping.

“I broke down and cried to Allah, but my mother said I must fulfill my duty,” sobs now 19-year-old Adiya, snatched at 17 to be a second wife. “My husband invoked the Prophet's teachings, saying it was my place to serve.”

Weaponized scripture adds metaphysical weight convincing victims and the community to view even the protest itself as profane. It also discourages relatives from intervening once a religious ceremony completes the act under sacred auspices. Destiny is seen as sealed - escape only comes through spiritual defiance.

This religious distortion continues slowly modernizing faith communities’ longtime struggle to calibrate theology against ethical human rights. But its lingering grasp still brings wreckage today in the form of broken Kyrgyz women.

Corrupt and Apathetic Authorities

Kyrgyzstan formally banned bride kidnapping in 2013. Yet despite this milestone, on-the-ground enforcement remains lacking, particularly in conservative rural areas where local officials collude to sustain the practice.Some authorities abdicate responsibility using familiar tropes around tradition, claiming internal family matters lie beyond intervention. Many prove simply apathetic to activities largely affecting “only” the female half of constituencies.

“The police kept saying they could do nothing,” despairs Burulai, remembering her pleas after her own abduction five years ago at age 17. “That it was a private affair now.”

Even more disheartening are direct allegations of obstruction and abuse against certain officials in regions where ala kachuu incidents remain ubiquitous. Some purportedly stonewall investigations of reported kidnappings, allowing crucial trials to disappear.

“When we went to officials, they just mocked us,” says Erbol, a volunteer with advocacy groups seeking justice. “They said brides cry rape whenever a marriage sours.”

In Kyrgyzstan’s remote hinterlands, a lack of impartial and ethical law enforcement keeps archaic customs rumbling forward. And for scores of women and girls, official negligence amounts to continued state enablement of what remains, despite excuses, a criminal act.

Seeds of Change

|

| A 2018 performance of children from the Center of Children’s Protection on bride kidnapping in Kyrgyzstan | UN Women |

Yet as more find the courage to speak out, the tide is shifting. Growing agitation against ala kachuu has birthed networks of shelters and activists committed to defending victims. Campaigns of awareness are penetrating even rigidly traditional enclaves. The simple question “What if it happened to your daughter?” makes many ruminate on their own complicity, or at least apathy.

Legal banning has granted leverage for victims to make fresh charges stick, empowering more to flee from oppressive new households through threat alone. Younger minds especially find themselves increasingly torn between modern views of equality and the strictures of old generations still clutching to the rules of an obsolete moral code. Here lies the true front for change.

For there are always those who defend it still, cloaking infringement in the familiar mantles of religion or cultural righteousness. Yet no principle held sacred sanctions the denial of one’s personal liberty and choice. Traffickers and slavers also once leaned on similar arguments, their vile trades too steeped in history or economics to dare question. It is time to say enough.

A New Day Dawning

|

| Activists marched the streets of Osh, in Southern Kyrgyzstan, protesting early marriages, bride-kidnapping, and domestic violence | UN Women/Dildora Khamidova |

Kyrgyzstan now stands at a deciding precipice, one blighted tradition poisoning gender rights progress. Its strong yet oppressed women deserve fulfilled lives free from violence or society-bound servility against their will.

Ala Kachuu’s days are numbered, but obsolescence remains unfinished still. The work goes on, voices uniting to describe a country where personal consent defines marital unions, not kidnapping yesteryear’s method now properly named for what it is - an abhorrent violation of essential human rights.

Kyrgyz maidens deserve no lesser liberty to chart their own destinies upon womanhood’s doorstep than any young individual does. Through solidarity and open eyes, let a new day dawn.

0 Comments

Some comments may go through moderation before appearing and are subject to our community guidelines, which can be viewed here. NB: All times are in Pacific Standard Time (PST).